I arrived in Manila during monsoon season in

early August. Manila is in Luzon, the northernmost island of the more than 7,000

islands awkwardly formed into a country by the Colonial Spanish over 300 years ago.

Destroyed during World War II, it suffers the horrors of a modern day city too quickly

created in a third world culture. There are no reminders of ancient history, and

few traces of its colonial grace remain. What natural beauty it has to offer is hidden

by pollution and overshadowed by dense poverty and overpopulation .

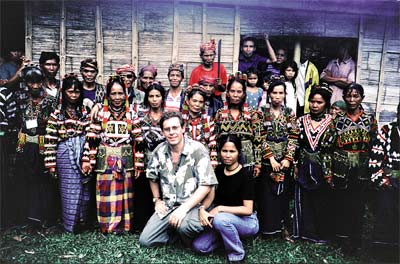

I was traveling to Tboli as part of a month-long

storytelling tour to gather stories. At that time my only encounter with Tboli tribes

had been the few paragraphs in The Philippine Handbook: "An estimated 200,000 Tboli inhabit the

Tiruray Highlands, a 2,000 square-km area within a triangle bounded by Surallah, Kiamba and Polomok..."

In Manila I found that any time I mentioned

my upcoming visit to Tboli I was greeted with tremendous interest, curiosity and

even awe. I was shown brass bells, beaded necklaces, photographs of elaborately costumed

women and treasured Tinalak wall hangings, the sacred ceremonial cloth of the T'Boli

Still, I felt a growing sense of unease. Why was I going to T'Boli? Was I to add

to the increased exploitation by mining, forestry and tourism? Worse, I knew nothing

of their traditions or taboos. My coffee reading was of no consolation, although

I often reflected on it.

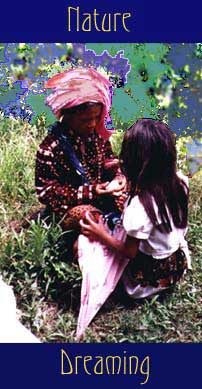

I have learned from my own travels and experiences

that an outer journey is an inner journey. The most unexpected occurrences are usually

the most significant, and the actual map is a secret map whose contours depend on

my own receptivity to what unfolds moment to moment. I considered my journey to T'Boli

a quest, a pilgrimage to a way of life rapidly vanishing from our planet.

In Manila, I said to myself, "It is best

to surrender to the fact that I know nothing and remain alert." In fairy tales,

esoteric and symbolic stories, it is the fool who becomes the hero or heroine. Sent

out into the world, she does not know in which direction to travel. So she shoots

an arrow, throws a stone, or a feather.

Where it lands is the direction in which she

journeys. I spent one week in Manila, hosted by the kindness and hospitality of the

most lovely people in the world, surrounded by the shock of unending, miserable poverty

and an unbreathable atmosphere. I looked forward to my trip south.

![]()